Building Machines that Learn and Think Like People (pt 2. Challenges for Building Human-Like Machines)

31 Dec 2017 | reviewtags: cognitive-science, machine-learning, brain, deep-learning Note: Ideas and opinions that are my own and not of the article will be in an italicized grey.

Series Table of Contents

Part 1: Introduction and HistoryPart 2: Challenges for Building Human-Like Machines

Part 3: Developmental Software

Part 4: Learning as Rapid Model-Building

Part 5: Thinking Fast

Resources

Glossary

| Article Table of Contents |

|---|

| Hand-Written Character Recognition |

| Atari Game Frostbite |

| References |

In the first post of this series, I left you with the question of whether generic neural networks with minimal constraints and inductive biases could learn and think in a human-like manner given sufficient data. This is actually a point of contention between people in the field, with some citing the pervasive cortical micro-column as evidence for highly regular structure across the brain, and others arguing that this is an extreme view.

The authors of this paper come from the perspective that the idea that the brain is a collection of general purpose neural networks with few constraints is extreme. Instead they believe that the brain relies on inductive biases. To showcase this and present the bedrock for their “key ingredients” for intelligence, the authors describe two examples where modern neural networks fail to learn like humans.

Hand-Written Character Recognition

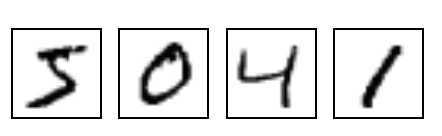

A popular training dataset for neural networks is the MNIST dataset, where the task is to learn to predict the digit that is on an image.

There are 10 digits in the training set (0-9), and each digit has 6,0000 examples. Many machine learning algorithms (not just neural networks) can achieve remarkable performance on this task. However, to achieve this remarkable performance, they learn to differentiate characters using thousands of examples. (Lake et al., 2016) argue that humans on the other hand can learn digits with far fewer examples. Further, we not only learn to recognize a digit, we learn a rich, structured representation or “concept”” for a digit, which we can then generalize to new tasks beyond recognition.

(Lake et al., 2016) argue that character recognition is a good domain to compare human and machine performance because, in general, characters lie on a simple-2D space (and are thus easy to analyze) and are often presented un-occluded. Of all object recognition tasks, this has the most promise for the development of a human-like algorithm in the near future. However, to learn as richly as humans do, machine learning algorithms will need to learn differently from how they currently do.

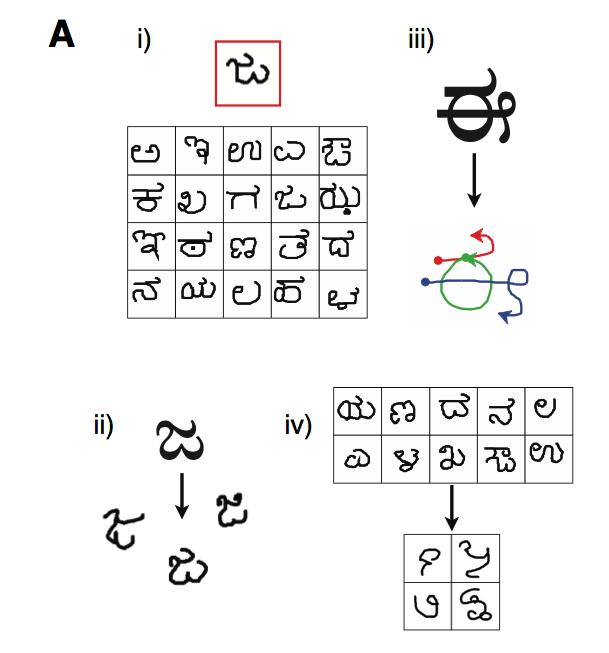

To address this challenge, the authors proposed that human-like algorithms be developed for the omniglot dataset presented below (Lake et al., 2015).

This dataset has dozens of classes with about 20 examples each (as opposed to only 10 classes with thousands of examples each). This is a better benchmark because it requires an algorithm to have the human ability of learning to recognize a character from only a few examples. Because humans create concepts for digits, they can generate new examples of characters they have little experience with (ii); they can show the essential abstractions of a character they’ve learned (iii); or they can generate new characters similar to a character they’ve just seen (iv). Essentially, this dataset tests an algorithm’s ability to learn a lot from very little - a quintessential human ability, and something lacking from deep learning based models.

Temporal Planning and Building on Prior Knowledge in Atari Games

Another recently popular domain for neural networks is playing video games. Google Deepmind recently released a breakthrough paper, Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning (Mnih et al., 2015), where they showed that a neural network trained via a reinforcement learning algorithm, known as the “Deep Q-Network” or “DQN”, was able to play numerous video games at “human-level”. Two things are worth noting. First, the algorithm they used, known as “Q-Learning”, is a variant of an algorithm which has been shown to be used by the brain (Niv, 2009). Second, despite its brain-inspiration, this algorithm was not capable of transferring skills across games and rather learned to play each game separately from scratch.

While the DQN did well on some games, others were particularly difficult for it. Particularly notable were games that required temporally extended planning strategies, i.e. planning at multiple temporal resolutions. (See here for examples of the importance of planning at multiple temporal resolutions for humans). Additionally, even when the DQN performed well, despite its brain-inspired architectural and algorithmic choices, it didn’t seem to learn like a human. For example, the DQN required approximately 924 hours of game play per game to do well, whereas humans could do well after approximately 2 hours.

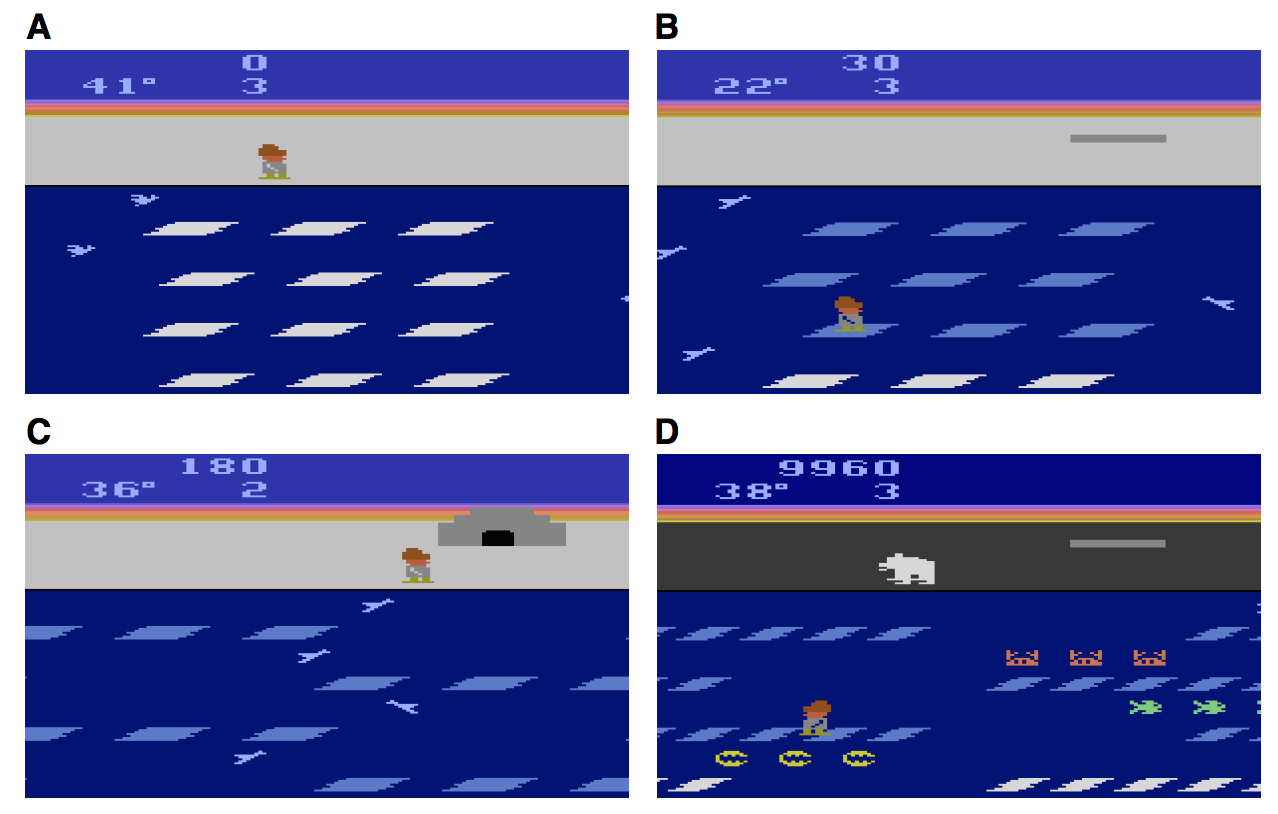

As a case-study to understand how this model’s learning differs from a human’s, the authors study learning for the Atari game, “Frostbite”.

In Frostbite, the user must hop around floating ice floats while avoiding obstacles (such as crabs seen in D). Ice floats can either be blue and inactive, or white and active. Hopping on an active ice flow deactivates it and constructs a piece of an igloo (seen in C). Once it’s constructed, the user must jump to it to complete the level.

Challenges. This game is challenging for a number of reasons. First, the environment is dynamic as ice floats and obstacles are constantly moving. This requires that the user re-plans their trajectory at every time-step. Second, the user must coordinate and relate sub-goals of hopping on active ice floats with the super-goal of constructing and entering an igloo. This requires planning at multiple temporal resolutions. Last, new rewards and obstacles present themselves as the levels advance. The ability to do object recognition & inference on objects then becomes very useful. Currently, the DQN needs to experience that something is good or bad in order to pursue or avoid it. If a new variant of an enemy appears, it must experience punishment to learn to avoid it. Humans, however, can infer that this new variant is likely negative for them from prior related experience.

Since this paper was released, numerous improvements over the DQN have been released. While learning has been dramatically improved, it is still not at the speed of human-learning. Some insights for why come when you look at the first few minutes of game-play. Here, the AI model is essentially random. A human, on the other hand, quickly learns the basics of the game: goals, sub-goals, object classifications, etc. For example, in Frostbite, a human quickly learns that you build an igloo by jumping on active ice floats while avoiding obstacles and enemies. The authors theorize that in order to accomplish this, humans are adopting intuitive theories to build models for model-based planning (intuitive theories are discussed more in the next section).

More insight into how machines still lack human-like learning comes from comparing how the DQN learns to compete levels against how humans learn to do so. In frostbite, the DQN learns sub-goals through incremental feedback in the form of points awarded for jumping on activated ice floats. Afterwards, once it randomly decides to enter the completed igloo, it learns that the objective is to enter the igloo. In other games, such as Montezuma’s revenge, where sub-goals do not have associated feedback, the DQN barely learns to leave the first level of the game and performs far below human performance. Humans on the other hand seem to have the ability to figure out super-goals without incremental feedback. This somewhat demonstrates the necessity, or at least the utility, of model-based planning that seems to underlie human learning. (One should note that a non-model based algorithm which simply attempts to explore as much of the level as possible was able to perform very well on Montezuma's revenge (Bellemare et al., 2016).)

Finally, another striking difference is found when comparing how the DQN and how humans re-purpose what they learn. After training, a human has learned a sufficiently rich representation of the game that

- Slight physical changes to game objects (such as color changes) have minimal impact on performance whereas DQN performance drops dramatically. (This is partially addressed with the biologically more plausible "schema" network released by Vicarious.(Kansky et al., 2017))

- A human can use their model of the game to perform well on arbitrary new tasks whereas the DQN is severely limited in this regard. Some fun(ny) examples by the authors include:

- Beat your friend, who’s playing next to you, but barely, not by too much, so as to not embarrass them

- Pass each level at the last possible second

- Touch each ice float once and only once

In order to build machines that learn like humans, we need to address the appropriate problems. Human learners fundamentally take on different tasks than today’s neural networks, and if we want to build machines that learn and think like people, they must address tasks that humans do. The comparison above is unfair because humans extensively utilize rich representations of prior knowledge whereas the DQN learns completely from scratch. However, humans rarely learn tasks from scratch, at least not since infancy. To work towards human-like learning, one key question is, “how do we learn rich representations of knowledge that may be re-purposed for new tasks so that they can be solved quickly?”

References

- Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Gershman, S. J. (2016). Building Machines That Learn and Think Like People. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40, 1–101.

- Lake, B. M., Salakhutdinov, R., & Tenenbaum, J. B. (2015). Human-level concept learning through probabilistic program induction. Science, 350(6266), 1332–1338.

- Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., Rusu, A. A., Veness, J., Bellemare, M. G., Graves, A., Riedmiller, M., Fidjeland, A. K., Ostrovski, G., Petersen, S., Beattie, C., Sadik, A., Antonoglou, I., King, H., Kumaran, D., Wierstra, D., Legg, S., & Hassabis, D. (2015). Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature, 518(7540), 529–533.

- Niv, Y. (2009). Reinforcement learning in the brain. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 53(3), 139–154.

- Bellemare, M., Srinivasan, S., Ostrovski, G., Schaul, T., Saxton, D., & Munos, R. (2016). Unifying count-based exploration and intrinsic motivation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 1471–1479.

- Kansky, K., Silver, T., Mély, D. A., Eldawy, M., Lázaro-Gredilla, M., Lou, X., Dorfman, N., Sidor, S., Phoenix, S., & George, D. (2017). Schema Networks: Zero-shot Transfer with a Generative Causal Model of Intuitive Physics. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1706.04317.