Building Machines that Learn and Think Like People (Glossary)

23 Dec 2017 | reviewtags: cognitive-science, machine-learning, brain, deep-learning Note: Ideas and opinions that are my own and not of the article will be in an italicized grey.

Series Table of Contents

Part 1: Introduction and HistoryPart 2: Challenges for Building Human-Like Machines

Part 3: Developmental Software

Part 4: Learning as Rapid Model-Building

Part 5: Thinking Fast

Resources

Glossary

Deep Learning

Also Neural Networks, Artificial Neural Networks

A model vaguely resembling a biological neural network that learns how to map inputs to outputs. For example, suppose you give it images of cats and dogs as inputs and the labels “cat” and “dog”, respectively. It will learn to predict the label “cat” when given cat images and “dog” when given dog images.

Also, I use “Neural Networks”, “Artificial Neural Networks”, and “Deep Learning” interchangeably. They all refer to artificial neural networks. When referring to the brain’s networks, I say “biological neural networks”.

Causal Models

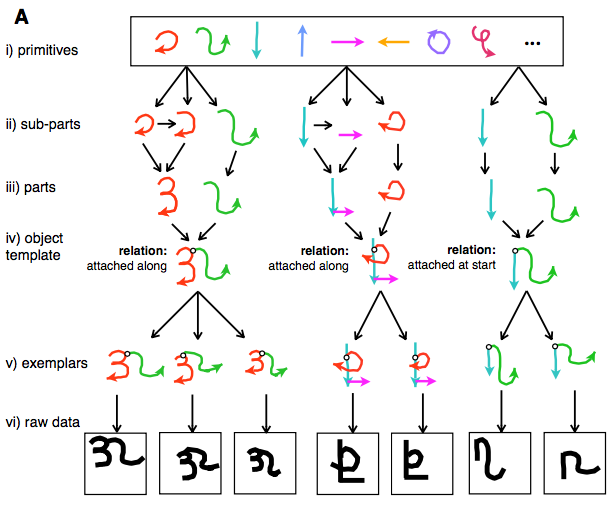

Causal models attempt to abstractly describe the real world process that produces an observation. For example, the model below represents drawing characters as combining strokes of a pen in a particular sequence.

Generative models

Generative models attempt to describe a process for generating data. However, unlike causal models, they do not attempt to model the real world process that generated the data. In the example of characters above, it would be sufficient if a generative model simply learned to predict the pixels associated with a character and not the strokes that might have produced it.

Inference

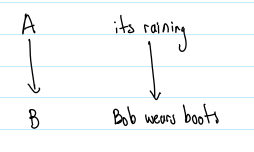

When A typically causes B, you can predict that B will come from A, and you can do inference that A was the cause of B. For example if A=”its raining” and B=”Bob wears boots”. You might see that it’s raining and predict Bob will be wearing boots or you might see that Bob is wearing boots and infer its probably raining.

Model-free, Model-based

Model-free algorithms use experience to directly learn quantities while model-based algorithms learn models for the world (such as probabilities for transitioning between world states). For example, learning an internal geographical map to get to work is “model-based”, whereas simply learning what turn to make at each corner but not remembering where each turn takes you is “model-free”. Model-based is somewhat preferred because you can use your learned map to plan a new way to get to work that is a composition of your previous routes.

Symbolic representations

Symbols can be thought of as variables that represent different quantities. For example, every letter of the alphabet can be seen as a symbol. Likewise, words in our vocabulary.

Sub-symbolic representations

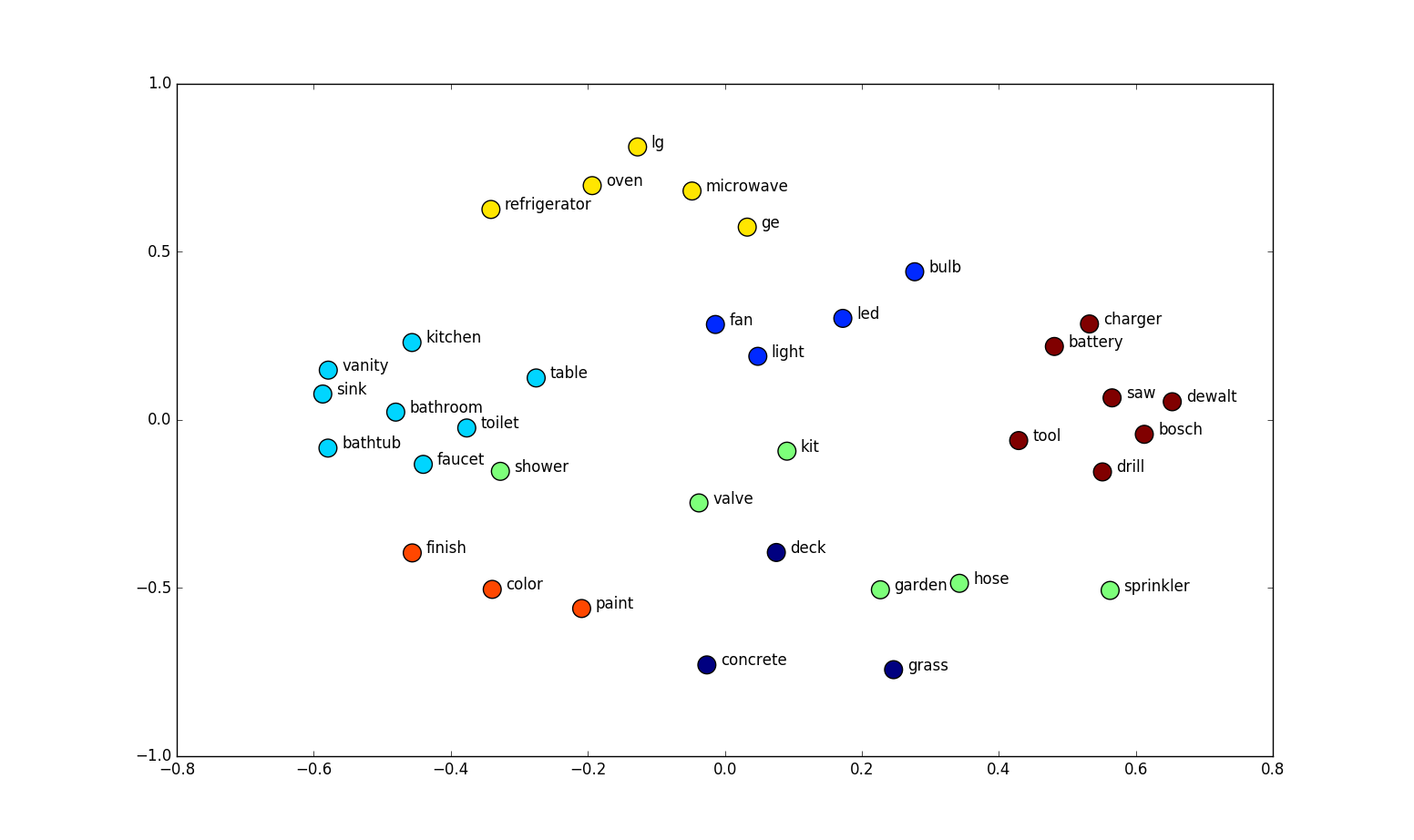

A representation is sub-symbolic if its constituents are not symbolic. For example, you could represent words as points in space like in the example below. Here, each constituent of the word is a real number (an x or y coordinate). This differs from a symbolic representation which would represent the words as symbols in and of themselves.

Distributed Representations

A distributed representation is one where different computational units hold different parts of a representation. In the example of neurons in a neural network, every neuron in a layer might by itself hold one aspect of a representation you care about. For example, in the plot above words are represented by 2 coordinates (x and y). Here, each neuron could hold the value for one coordinate (one neuron for x, the other for y), so the representation for the word is distributed across the neurons.

Inductive Biases

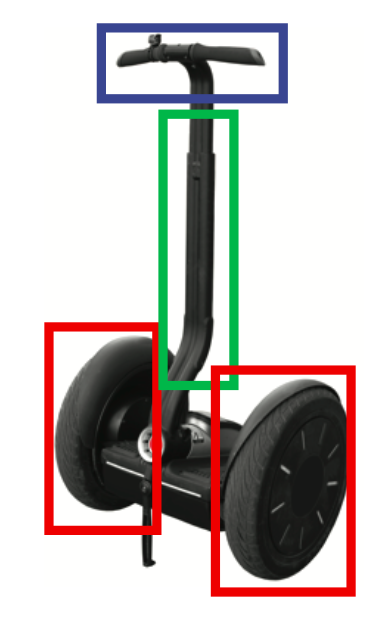

Inductive Biases are the assumptions your model makes about the relationship between its inputs and outputs for new, unseen inputs. For example, a model that learns to represent visual concepts might have the inductive bias that objects are composed of learnable parts and relations. With the example of the segway below, it could be decomposed into two wheels connected by a platform, which provides the base for a post, which holds the handlebars, etc.

Compositionality

Compositionality is the classic idea that new representations can be constructed through combinations of primitive elements. Real world examples include sentences which are combinations of words, the “primitives” of language, or programs which are compositions of functions, which are themselves compositions of more primitive data types.

Learning-to-learn

Learning-to-learn is the idea of using learned concepts as “primitives” for other concepts when learning. In the example of the segway above, you identify a segway more quickly by re-using the concepts you’ve already learned for wheels, platforms, posts, etc.